|

Book 'V2-VERGELTUNG' from The Hague |

Immediately after the start of the V2 activities, the British Bomber Command carried out heavy bombing attacks on 14th and 17th September 1944 on targets in Wassenaar. When these attacks seemed to achieve no success, they reverted to precision attacks with Spitfires. These fighter bombers carried two 250 pound bombs and attacked with 20 mm guns. Although these air attacks interrupted the V2-activities, they couldn’t stop the launchings. In the months of January up to March 1945 the Germans had a rather constant rate of firing of some 230 rockets per month, in spite of the fact that the fighter bombers of the RAF were by now able to operate longer above The Hague region, because of the ability of airfields in the now liberated Brabant.

Because the fighter bomber hardly had any success in disturbing the launching installations, they turned their attention to the vulnerable railway infrastructure. On 11th December 1944 the railway station at The Hague Staats Spoor was bombed, whereby 3 tons of high explosive bombs were dropped. Also bombing was carried out on a railway viaduct near Leiden and the railway station was destroyed. Locomotives in particular were targeted, as these were more difficult to replace than a railway track. Statistics of the number of launches however show, that none of these actions affected the launches.

In the woods near Ommen two one kilometre long camouflaged rail tracks were laid out. The trains loaded with V2-rockets, bound for the launching sites in the western part of the Netherlands, stayed there during the day to protect them against the Royal Air Force. The trains continued their journey at night to Leiden, where they were parked during the day until dusk. Then they carried on to the station Herensingel [transfer point]. In the early morning further transport took place with the Vidal trailers.

In the beginning of December 1944 the Mayor of Wassenaar issued a statement, on the orders of the Wehrmachtskommandant, saying that from 5th December owners or managers of ground and buildings on through-going roads must ensure that all street-side entrances and all nearby sheds and garages must remain open. The entrances must be marked on both sides with white planks or bales of straw. Where there were no sheds etc. the immediate vicinity of the houses were to be kept free to allow vehicles the opportunity to shelter. This

order applied for the Van Zuylen van Nijenveltstraat, Rijksstraatweg and the Katwijkseweg. The marking of camouflaged shelters with bales of straw or white planks applied also in Warmond, Voorschoten

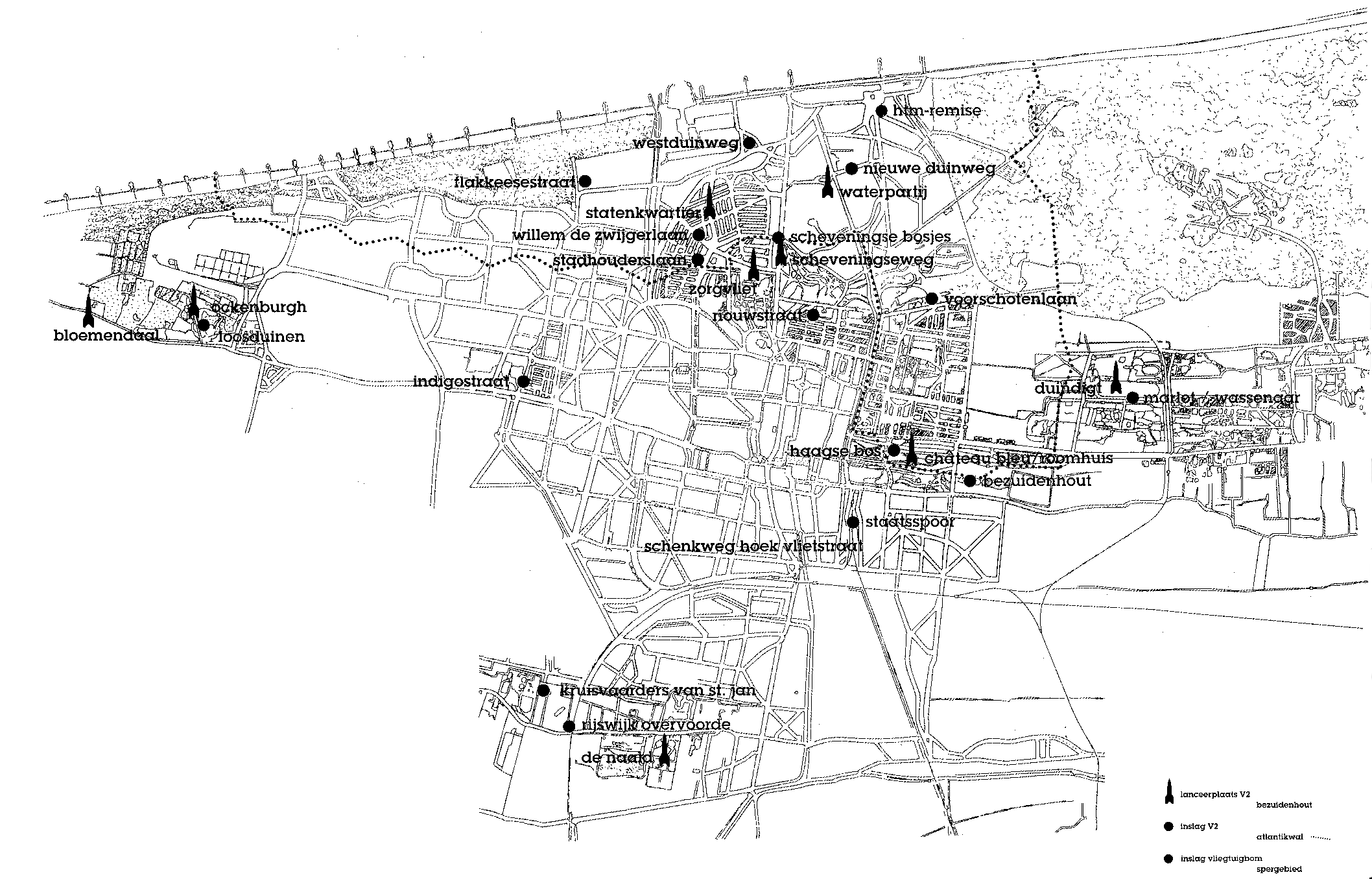

View of Loosduinen, The Hague and Wassenaar.

Marcel Prins designer, The Hague13 .

were to be kept free to allow vehicles the opportunity to shelter. This order applied for the Van Zuylen van Nijenveltstraat, Rijksstraatweg and the Katwijkseweg. The marking of camouflaged shelters with bales of straw or white planks applied also in Warmond, Voorschoten and Katwijk. By these measures, the V2-transports could take shelter, if Allied reconnaissance or fighter planes came over.

Further to the east, in Germany, the largest railway junctions were bombed daily and completely destroyed as a result. Herewith the Allies hoped to stop the supply of rockets from the production centres. By employing thousands of forced labourers, the Germans were soon able to repair the damage on the railway sites, so that at least two tracks were available. The trains with rockets and liquid oxygen could still carry on14, although there were fewer rockets going to the launching sites than were being produced. By the end of September only 2000 m3 liquid oxygen arrived daily by rail in the operational area of the western part of the Netherlands. This was barely enough for launching 24 V2s.

Early in February 1945 the Royal Air Force carried out air attacks on the launching sites. Also the depot of the Westland Steamtram Company (Westlandsche Stoomtram Maatschappij) was bombed. It was suspected that rockets were stored there. The depot was damaged, but remained in use. With the bombardment on 6th and 9th February the Hovy district was hit and badly damaged. The market gardens were not spared; for instance that of the firm Klinkenberg. In total 14 tons of high explosive bombs were dropped.

At least 11 camouflaged V2s could be seen on an air photo made by the RAF of The Hague’s City Forest (Haagse Bos). These rockets were not armed and still had to be made operational.

On 3rd March 1945 the Royal Air Force wanted to terminate the V2 threat in one big blow.

However, instead The Hague’s residential area Bezuidenhout was bombed. The attack failed and the same night rockets were launched again. On the nights of 3rd and 4th March 1945 one of the V2s plunged down on the corner of the Schenkweg and the Vlietstraat. Hereby eight firemen from The Hague lost their lives.

Apparently the pilots had received incorrect instructions, and therefore the British bombs, a total of 86 tons of high explosive fell not on The Hague’s City Forest, but on the densely populated area of Bezuidenhout, a suburb of The Hague. More than 500 people were killed and over 200 people were wounded. About 30.000 people lost their home (more than 5% of the total population of The Hague). The Bezuidenhout area was at that time more densely populated than usual, because a large number of evacuees were quartered there. These evacuees came from the coastal zone of The Hague and Wassenaar (Sperrgebiet), and also the expulsion from the launching sites. The bombings destroyed 220,000 square metres of built-up area. Therefore, a huge number of inhabitants needed re-housing, which was mainly effected in the central and eastern parts of the Netherlands.

The moment the British realised the impact of the disaster, they dropped flyers above Bezuidenhout, apologising for the fatal mistake. The Dutch resistance newspaper Trouw complained about the bombings:

‘The horrors of the war are increasing. We have seen the fires in The Hague after the terrible bombings due to the V2-launching sites. We have seen the column of smoke, drifting to the south and the ordeal of the war has descended upon us in its extended impact. We heard the screaming bombs falling on Bezuidenhout, and the missiles which brought death and misery fell only a hundred metres from us. At the same time we saw the launching and the roaring, flaming V2, holding our breath to see if the launch was successful, if not falling back on the homes of innocent people. It is horrible to see the monsters take off in the middle of the night between the houses, lighting up the skies. One can imagine the terrors that came upon us now that The Hague is a frontline town, bombed continuously for more than ten days. Buildings, burning and smouldering furiously, a town choking from smoke, women and children fleeing, men hauling furniture which they tried to rescue from the chaos. What misery, what distress’.

[Quote from the resistance newspaper Trouw]

On March 18th, 1945 six British Spitfires carried out an air raid on the office building of the BPM (Bataafsche Petroleum Maatschappij)15 in The Hague. The building was used by the German Air Force (the Luftwaffe) to accommodate communication equipment. By destroying this equipment the British hoped to paralyse the command centre and communications control for the V2 operations. The buildings and installations were partly damaged, but this did not stop the rocket launching.

On several occasions, the resistance gathered intelligence on German activities in the tram depot in the Zwolsestraat and in the nearby Ford garage. These activities were mainly related to the V2-weapon. The RAF carried out a bombing raid on March 22nd, 1945, where mainly the houses on the Zwolsestraat were hit. In this attack 20 tons of high explosives were dropped. Because of the evacuation of the coastal area as an out of bounds area (Sperrgebiet) there were no civilian victims.

Based on information received from the resistance, the following targets were attacked: the assembly point near De Wittenburg, the storage building in Rust en Vreugd, and the launching sites on Duindigt. The raids and bombings caused the death of several of Wassenaar’s inhabitants and more than 100 were wounded. As it became apparent that the Spitfire air raids could not sufficiently paralyse the German V2 operations, ground surface bombings were carried out on a large scale. On March 9th the Duindigt estate was heavily bombed after the unsuccessful bombings on March 3rd 1945. The Germans operated alternatively no less than 30 launching pads on the estate. This time the bombings of the British Spitfires were successful: a number of rockets kept ready for launch were damaged. The Germans ultimately left Duindigt.

Borsboom, J.A.M.: Geheime V2’s waren oorzaak bombardement Bezuidenhout. Bij de produktie vonden reeds duizenden dwangarbeiders de dood. In: Nederlandse Historiën, Tijdschrift voor vaderlandse (streek)geschiedenis, Vol. 30, No. 2, May 1996, p. 58-63.

Borsboom, J.A.M.: Gevolgen van de V2-raketlanceringen voor Den Haag. In: Bezuidenhout Koerier, Vol. 13, No. 4, 18 May 2000, p. 7-9.

Collier, B.: The battle of the V-weapons, 1944-45. 1964.

Korthals Altes, A.: Luchtfotojacht op Vergeldingswapens in Nederland 1944-1945. In: Spiegel Historiael, Vol. 19, No. 3, March 1984, p. 114-119.

Korthals Altes, A.: Luchtgevaar. Luchtaanvallen op Nederland 1940-1945. Amsterdam, 1984.

To the footnotes page

Back to Table of Contents

First English edition, Almere – The Hague, August 2005

Translation: Dily Damhuis, Paul Fowlie, Sylvia en Johan van Oosten en

Trees Teunissen.

Original Dutch version published, Almere – The Hague, September 2003 (2nd edition)